(English version of this interview below)

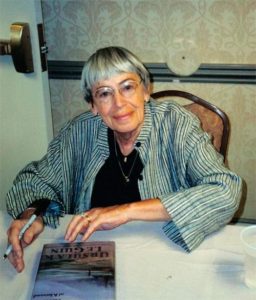

Ursula K. Le Guin (Ursula Kroeber Le Guin), nació en Berkeley (California), el 21 de octubre de 1929, en el seno de una familia sin problemas económicos. Las respectivas profesiones de sus padres tendrían un efecto considerable en la joven Ursula: su madre era escritora de cuentos infantiles, y su padre antropólogo. Su educación, eminentemente académica, la llevó a interesarse por la lectura y la escritura, y a los 11 años envió un manuscrito a la conocida revista Astounding Science Fiction, que fue rechazado, pero el hecho nos da una idea del empuje creativo que ya se gestaba en la mente de Ursula. Ingresó en la Escuela Radcliffe de la Universidad de Harvard, en la que se graduó en el año 1951; posteriormente asistió un año a las clases de la Universidad de Columbia, en la que hizo un postgrado de lenguas romances. Tras finalizar este curso, consiguió la beca Fulbright, gracias a la cual pudo viajar y estudiar en Francia, donde conoció al que sería su marido hasta ahora, Charles Le Guin, con quien se casó en 1953 y con quien tendría tres hijos. Más tarde volvió a los EE.UU. y comenzó la que sería una larga carrera literaria.

Esta “gran dama” de la fantasía y la ciencia ficción completa una de las carreras más variadas de estos géneros: desde la poesía hasta los libros infantiles y los ensayos, nada se resiste a Ursula K. Le Guin. A lo largo de su actividad como escritora, ha ganado varios premios Hugo y Nebula, y fue galardonada Gran Maestra por la Asociación de escritores Estadounidenses de ciencia ficción y fantasía (SFWA), la primera mujer en conseguirlo. Ha publicado seis libros de poesía, veinte novelas, más de cien relatos, cuatro colecciones de ensayos, once libros para niños y algunas traducciones poéticas y políticas. Ursula K. Le Guin se confiesa feminista, pacifista y taoísta, y sus obras se tiñen de sus convicciones sutil pero eficazmente. Actualmente vive en Portland (Oregón, EE.UU).

Tras publicar varias historias, su primera novela, El mundo de Rocannon (1966), una obra de ciencia ficción que se convertiría en una serie, continuada por Planeta de exilio (1966), La ciudad de las ilusiones (1967) y la obra que le dio el reconocimiento internacional, La mano izquierda de la oscuridad (1969), con la que ganó un Hugo y un Nebula.

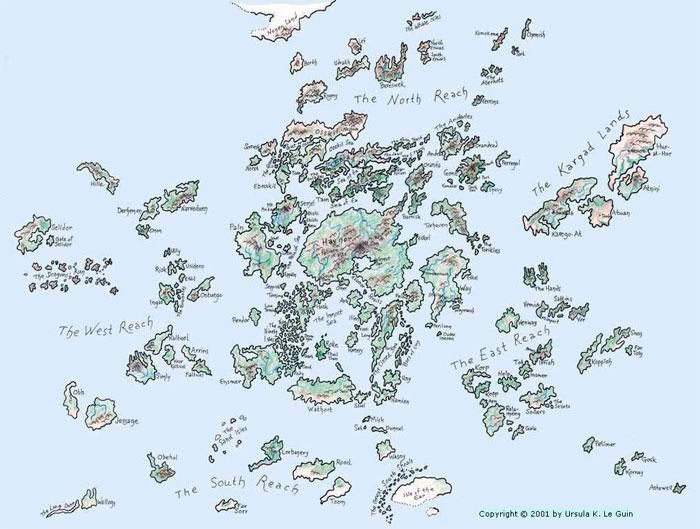

En 1968 inició su saga más conocida, y por la que entraría en la puerta grande en el género fantástico, tras sorprender en el ámbito de la ciencia ficción. Con la primera novela de la saga, Un mago de Terramar, continuada en 1971 por Las tumbas de Atuan y La costa más lejana, la escritora estadounidense se convirtió en un referente para los amantes del género que J.R.R. Tolkien “reinventó” en 1954 con la publicación de El Señor de los Anillos. La saga continuaría en 1990 con Tehanu, y en 2001 con En el otro viento. Todos los libros de Terramar podéis encontrarlos en la antología «Historias de Terramar, Edición Completa«, que Minotauro publicó en noviembre de 2006 en una magnífica edición y que tuvo a bien enviarnos.

Tras finalizar su primera etapa con Terramar, Ursula K. Le Guin volvió a resurgir con El nombre del mundo es Bosque (1972), con la que el año siguiente conseguiría el premio Hugo, y Los desposeídos: una utopía ambigua (1974), sin dejar de lado la ciencia ficción, con «La rueda celeste» (1971), «El ojo de la Garza» (1983) y «El eterno regreso a casa» (1985).

El año pasado publicó en España, también de la mano de Minotauro, Los Dones (Gifts), que obtuvo un PEN Center USA de Literatura Infantil en el 2005, y que significa el inicio de la saga de La Costa Oeste (Western Shore), que continúa con Voices (Voces), aún no publicado en castellano, y culminará con Powers (poderes), aún no editado en inglés.

Fantasymundo ha intentado acercarse a la vida y obra de Ursula K. Le Guin a través de diferentes artículos, como el reportaje sobre su saga Terramar, o la reseña de «Cuentos de Terramar«, pero necesitábamos hablar con la autora para conocer mejor sus motivaciones. He aquí nuestro diálogo con ella en castellano e inglés:

Alejandro Serrano: La imagen típica de un escritor, sobre todo si tiene cierta reputación y una prolífica carrera internacional, es de una persona habitualmente sentada en su sillón favorito, dando vida a diferentes personajes, alejada del mundo. Sin embargo, sus libros muestran que su vida es mucho más intensa que todo eso, su imaginación tiene fuertes tintes sociales y un profundo conocimiento de la naturaleza humana… ¿cómo pasa sus días Ursula K. Le Guin? ¿Qué experiencias en su vida o qué libros han marcado su concepto de la fantasía?

Ursula K. Le Guin: me temo que, como la mayoría de escritores, Ursula pasa casi todos los días sentada enfrente de un escritorio, con un cuaderno de notas o un ordenador sobre él. Mi vida no es muy emocionante –para nadie-, pero para mí está llena de pasión, ansiedad, alegría, tristeza,… tanto que me asombra pensar en ello.

Ya escribía historias fantásticas cuando tenía ocho años de edad, así que no creo que mis experiencias vitales sean la base de mi forma de escribir fantasía. Simplemente, mi mente funciona así. La “razón pura” es inaccesible para mí; mi razón trabaja a través de la imaginación.

Alejandro Serrano: La primera vez que alguien me habló de Terramar, hace mucho tiempo, la describió como “una muy buena saga de fantasía pero demasiado feminista”. Siempre sospeché de las etiquetas, así que ese comentario reforzó mi intención de leerla. Y no sé cual fue su intención al iniciar la saga, pero creo que intentó reclamar la imagen de la mujer en la fantasía pero sin olvidar al hombre, especialmente a aquel que respeta a la mujer y su papel en la vida. ¿Estoy equivocado? ¿Cree que la fantasía actual ignora bastante más el género de los personajes para centrarse en su psicología? Hoy en día hay muy pocas Éowyns por ahí, la mayoría de los personajes femeninos en los libros actuales toman roles protagonistas por derecho propio, no sólo como complemento del varón. No esperan a sus hombres cosiendo y suspirando, afortunadamente.

Ursula K. Le Guin: No estás equivocado, pero debes recordar que comencé a escribir Terramar en 1968, cuando no había mujeres en la fantasía heroica, tan sólo Éowyns. De hecho, había pocas mujeres en la literatura, tan sólo Emma Bovarys. Los libros trataban sobre los hombres, que hacían cosas propias de su género; las presencia de las mujeres era marginal, y tan sólo eran concebidas en su relación con los hombres. “Un mago de Terramar” no pone en cuestión eso en absoluto. El siguiente libro, “Las tumbas de Atuan”, sitúa a la mujer como centro, acompañada de un hombre: ninguno de los dos puede lograr su libertad sin el otro. “La costa más lejana” vuelve al mundo de los hombres. Los últimos tres libros de la saga miran al mundo de los hombres pero poniendo sus fundamentos morales bajo una lupa, a pesar de su realidad.

Ursula K. Le Guin: No estás equivocado, pero debes recordar que comencé a escribir Terramar en 1968, cuando no había mujeres en la fantasía heroica, tan sólo Éowyns. De hecho, había pocas mujeres en la literatura, tan sólo Emma Bovarys. Los libros trataban sobre los hombres, que hacían cosas propias de su género; las presencia de las mujeres era marginal, y tan sólo eran concebidas en su relación con los hombres. “Un mago de Terramar” no pone en cuestión eso en absoluto. El siguiente libro, “Las tumbas de Atuan”, sitúa a la mujer como centro, acompañada de un hombre: ninguno de los dos puede lograr su libertad sin el otro. “La costa más lejana” vuelve al mundo de los hombres. Los últimos tres libros de la saga miran al mundo de los hombres pero poniendo sus fundamentos morales bajo una lupa, a pesar de su realidad.

Sin embargo, la palabra “feminista” ha sido malinterpretada y denigrada, y al feminismo hemos de dar las gracias de la inclusión en la literatura de todo el género humano, no solamente de su mitad masculina.

Lo cierto es que las mujeres aún tienen más posibilidades de terminar al cuidado de la casa que los hombres –quizá cosiendo, quizá suspirando, quizá estudiando matemáticas o tocando la viola, pero casi siempre al cuidado de los niños, poniendo la comida en la mesa o limpiando el suelo. ¿Hay que avergonzarse de ello? ¿En qué hace a la mujer inferior al hombre dedicarse a esas tareas? Las mujeres no tienen porque imitar al hombre para ser consideradas seres humanos.

Durante mucho tiempo, la ficción falló precisamente en eso, en preguntarse que ocurre en el hogar, entre las mujeres. Si está cosiendo, ¿porqué lo hace? ¿Quiere hacer esto o no? ¿Porqué deshace el tapiz cada noche? ¿Suspira por su amante ausente, o por el estado de la economía del país, o el problema del origen de la maldad? ¿Cómo es la vida, la actual vida interna de la mitad de la raza humana?

Si a un hombre no le interesan las respuestas a estas preguntas, dejemos que lea libros para chicos sobre batallas, etc. Hay muchos de este tipo.

Alejandro Serrano: Su trabajo en Terramar y otras novelas se centra habitualmente en la maduración de sus personajes, y en sus esfuerzos por encontrar su lugar en un mundo cruel lleno de peligros, cuyo equilibrio tiende a ser volátil… Esto es únicamente un reflejo de la vida real, transplantado a un mundo lleno de criaturas sobrenaturales, y que realza aún más la universalidad de los temas sociales de sus libros. La mayoría de la fantasía suele centrarse en héroes sin escrúpulos o en escenas donde la espectacularidad eclipsa toda reflexión. Algunas veces parecen intentos por esconder la falta de argumentos del escritor, pero sus libros se centran por completo en estas reflexiones… ¿La fantasía debería hacernos pensar sobre el mundo real, sobre nuestra relación con el resto del mundo?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Dudo mucho a la hora de afirmar que cualquier tipo de literatura “debería” hacer algo; esto reduce al arte a la practicidad –enseñando, inculcando moral-, como si fuese su única función posible. Así que diría sólo que la fantasía que no explore de alguna forma metafórica nuestra propia existencia en el mundo, probablemente resulte trivial. No obstante, también puede ser divertida.

Alejandro Serrano: El papel de la mujer y el hombre en la sociedad occidental ha cambiado mucho en las últimas décadas, y ambos espacios vitales se han aproximado mucho, pero… algunas veces parece que si no estamos casados, no tenemos niños o relaciones estables no podamos realizarnos como personas; y si tenemos niños, tanto la mujer como el hombre han de trabajar fuera, sin tiempo para educarlos. ¿No cree que en muchas ocasiones se nos pide, a hombres y a mujeres, cumplir con su papel en el seno de la familia y en nuestro trabajo como si fuéramos superhéroes?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Sí. Veo lo duro que ha sido para la generación de mis hijos (ahora en los cuarenta) trabajar, cumplir con sus deberes, con muy poco tiempo para tomarse las cosas con tranquilidad; siento profundamente que algo está muy mal. Es el trabajo, y su naturaleza, los que están equivocados.

Creo que los hombres y las mujeres están atrapados en una gran máquina que ha convertido al mundo, la máquina del capitalismo, en la que la productividad, la actividad y el crecimiento no pueden parar ni un momento. Esta gran máquina cubre la tierra de residuos y devora a sus hijos.

Alejandro Serrano: Todos los libros de la saga de La Costa Oeste (‘Gifts’, ‘Voices’ y ‘Powers’), serán publicadas en España, según el editor de Minotauro. Por el momento, tan sólo han traducido el primero, “Los Dones”, una novela que explora la naturaleza de los poderes, el crecimiento personal y como éstos pueden entrar en conflicto con el resto del mundo. Nuestro conocimiento puede ser útil, pero también el origen de nuestra ruina. Esta lección está bastante lejos del trato que usualmente se le da en la literatura, como regalos sin condiciones: pero hemos de ser cuidadosos al usarlo, son peligrosos. No creo que estos libros estén dirigidos sólo a la audiencia juvenil, los adultos pueden aprender mucho de estas historias y aplicar sus lecciones en su vida real, en su relación con los demás. ¿Cuántos conflictos podrían haberse evitado si fuésemos más cuidadosos con nuestras diferencias?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Los editores adoran la categoría de “joven adulto”, que les proporciona ventas seguras entre los adolescentes. Desafortunadamente, si publicas un libro en esa categoría puedes estar seguro de que los críticos (incluso dentro de la ciencia ficción y la fantasía) lo ignoren, y que muchos adultos lo eviten, creyendo que tan sólo es para críos. El hecho es que, muchos libros para “jóvenes adultos”, particularmente en la fantasía, difieren únicamente del resto en que sus protagonistas suelen tener menos de veinte años.

Me gusta escribir sobre personas de esta edad porque son abiertos, vulnerables, su encuentro con el mundo es fresco y apasionado; pero ciertamente, no creo que mis libros con protagonistas jóvenes estén tan sólo escritos para adolescentes (después de todo, tan sólo hay que fijarse en “Romeo y Julieta”)…

Alejandro Serrano: Mientras esperamos por ‘Voices’ (“Voces”) y ‘Powers’ (“Poderes”) en España, Minotauro publicará a últimos de febrero de este año un libro con algunas historias suyas de ciencia ficción: “Los Mundos de Ursula K. Le Guin”, con ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ (“La mano izquierda de la Oscuridad”), ‘The Word for the World is forest’ (“El nombre del Mundo es Bosque”), and ‘The Dispossesed’ (“Los Desposeídos”). ¿Siente que hay diferencias sustanciales entre escribir ciencia ficción o fantasía? ¿Puede contarnos algo sobre estas historias?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Estas tres novelas son todas de ciencia ficción, no de fantasía; esto es así, se sitúan en un universo en el que se obvían las leyes de la física que conocemos, pero no violan abiertamente los principios científicos, tal y como hace la fantasía con sus magos, gatos alados o los Alephs.

Creo que la fantasía es la más antigua clase de literatura que todavía se practica, y la ciencia ficción la más reciente. La ciencia ficción es un derivado del realismo. Al igual que el realismo, usa el mundo actual como base, a menudo el contemporáneo. Difiere del realismo únicamente en la extrapolación de un futuro al que se puede llegar a través de la actualidad presente, o en imaginar algún plausible avance científico o cambio social, todo ello desarrollado de la forma más realista y preciosista posible. Es una forma de ficción altamente ingeniosa y divertida, que he disfrutado leyendo y escribiendo.

Creo que la ciencia ficción está cambiando de forma, perdiendo su esquema intelectual, mezclándose bajo otras formas, y tal y como el mundo cambia rápidamente a nuestro alrededor, la ficción no puede, literalmente, mantener este crecimiento de la ciencia y la tecnología, y sólo lo intenta.

Alejandro Serrano: Hay sectores en nuestra sociedad (y en EE.UU.), que intentan forzar a la población a abrazar ideas políticas que creíamos superadas, como el fundamentalismo religioso, los tabúes sexuales o su visión de la violencia justificada. Persiguen a todo el que no opina de la misma forma, y aseguran que el país sufre bajo la falta de moralidad… ¿Cree que existe una moral distinta del fundamentalismo político o religioso, más tolerante en términos sociales, con mayor libertad de pensamiento? ¿Qué papel tiene la fantasía en ella?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Diré únicamente que tanto la ciencia ficción como la fantasía son formas de lieratura que permiten imaginar ALTERNATIVAS. Sociedades, políticas, culturas, reglas de género, ideas religiosas,… todas ellas alternativas. Y precisamente por ello tienen un gran papel a la hora de cultivar el uso racional de la imaginación, en liberar a las mentes de la mano muerta de las ideologías rígidas e irracionales.

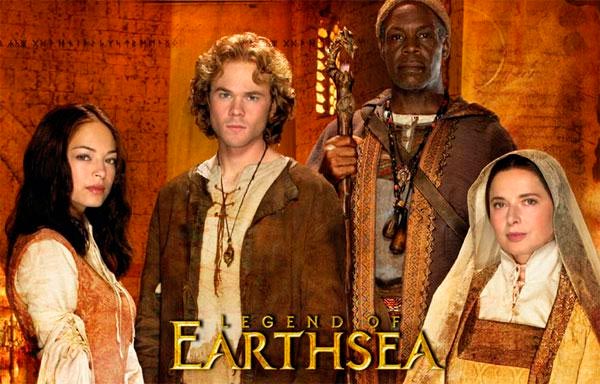

Alejandro Serrano: No sé que ocurre con las adaptaciones de Terramar. Francamente, no es tan difícil comprender al menos el espíritu de la saga (aunque haya muchas cosas interpretables), pero cada vez que alguien intenta adaptarla a otros formatos, el resultado no tiene nada que ver con lo que usted ha escrito. No sólo le ocurre a usted, obviamente, por ejemplo, hace poco Hollywood ha destrozado por completo “Soy Leyenda”, de Richard Matheson. Creo que no deberían adaptar un libro si no quieren preservar su espíritu. Las tres películas de “El Señor de los Anillos”, de Peter Jackson, son una excepción… hay muchos cambios en ellas, pero el espíritu de J.R.R. Tolkien está en ella. Incluso con el exceso de la violencia y la falta de las profundas reflexiones que sí están presentes en los libros, uno puede apreciar la belleza de la vida y lo que Sauron pretende destruir: miles de pequeñas historias personales, todo lo bueno que existe en el mundo, algo que está por encima de la supervivencia de cualquier reino. ¿Cree usted que en el futuro podremos ver una buena adaptación de Terramar, tras los intentos de Goro Miyazaki y Lieberman? ¿Nadie está interesado en su propio guión, que escribió junto a Michael Powell? ¿Qué piensa de las dos adaptaciones de Terramar y sobre la de El Señor de los Anillos?

Ursula K. Le Guin: ¡Ay, ay, caramba! ¡Por favor, no me preguntes sobre eso!

Alejandro Serrano: Parece que todo está dicho en Terramar, y en ocasiones ha expresado su rechazo a continuar la saga, algo muy entendible, por otra parte, tras años de dedicación a ella. Y francamente, aunque podría continuar, argumentalmente hablando, parece bien cerrada. ¿Ha pensado alguna vevz volver a escribir sobre Ged y Tenar, o algún spin-off sobre algún personaje?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Bien, como se suele decir, “Nunca digas nunca jamás”. Amo a la gente que habita Terramar, y hay muchas islas que nunca tuve la oportunidad de visitar… pero creo que la historia finalizó por sí misma por completo al final del sexto libro.

Alejandro Serrano: El trabajo de un escritor nunca parece finalizar, al menos si la inspiración acude… ¿qué proyectos tiene en mente?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Mi próximo libro, que se publicará esta primavera, se titula ‘Lavinia’. Es la chica italiana con la que Aeneas está condenado a casarse, y para poder fundar la ciudad y el imperio de Roma. Los últimos libros de la Eneida están llenos de batallas: Virgilio tenía bastante que contar sobre la guerra, su locura y tragedia, porque (creo), él quería mostrar a su nuevo emperador Augusto el coste real del Imperio y preguntarle: “¿merece la pena?”. Pero no tuvo tiempo de contarnos mucho sobre Lavinia, o al menos de dejarla hablar. Así que, leyendo el poema, comencé a preguntarme sobre ella, le dije: “¿Lavinia, quién eres?” Y ella me respondió. Y aquí está la novela. Es diferente a todo lo que he escrito hasta ahora. Esoy muy contenta con ella.

Y tras Lavinia no sé lo que haré, nunca lo sé.

Alejandro Serrano: Finalmente, ha sido un placer conocerla… ¿Qué diría a sus fans de Fantasymundo y a aquellos que aún no han leído sus libros?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Un escritor sin lectores es una criatura miserable. Si sois felices leyendo mis libros, creedme, ¡soy feliz porque los leéis! Y estoy feliz de haberos encontrado, en una forma misteriosa –la única magia auténtica que conozco-, en el espacio de la literatura, donde las mentes y la imaginación se encuentran, se unen y juegan juntas, y aunque seamos siempre extraños, aún más por hablar en distintas lenguas, nos comprendemos.

He disfrutado esta entrevista. ¡Muchas gracias!

Ursula

_________________________________________________

English version of this interview:

Alejandro Serrano: The archetypal image of a writer, especially with it has a certain name and a prolific international career, is a person constantly sitting in his (or hers) favorite armchair giving life to their characters, far away from the rest of the world. However, your books show that your life is much more intense than that, your imagination has strong social dyes and a deep knowledge of the human nature… How spends her days Ursula K. Le Guin? What experiences in your live or books have market your conception of fantasy?

Ursula K. Le Guin: I fear that, like most writers, Ursula spends a large part of her days sitting in front of a desk with a notebook or a computer on it.

My life is not a thrilling one — for anyone else – For me it is so full of passion, excitement, anxiety, joy, grief, etc. that it amazes me to think about it.

I was writing fantastic stories by the time I was eight years old, so I don’t think my experiences in life are the source of my fantasy. It is simply the way my mind works. “Pure reason” is inaccessible to me; my reason works through imagination.

Alejandro Serrano: The first time that someone told me about Earthsea (Terramar in spanish), a long time ago, he described it as «a very good fantasy saga but too feminist”. I have always suspected the labels, so that I decided to read it even more. And I do not know which was your intention when you initiate the saga, but I believe that you wanted to claim the image of women in fantasy but without forgetting the man, especially men that respects women and their roles in life. I’m wrong about it?

Do you think that the actual fantasy ignores a little more the gender of characters in order to focus on their psychology? Nowadays there are few Éowyns around there, most of the women’s characters in actual books are taking starring roles in their own right, not as an adjunct of male. They not wait at their homes sewing and sighing, fortunately.

Ursula K. Le Guin: You are not wrong about it, but you must remember that I began to write the Earthsea books in 1968, when there were no women in heroic fantasy stories, only Eowyns. In fact there were few women in literature, only Emma Bovarys. Books were about men, and the doings of men; women were marginal, and perceived only as they related to men. “A Wizard of Earthsea” does not put that arrangement in question at all. The next book, “The Tombs of Atuan,” puts a woman in the center together with a man: neither can attain freedom without the other. “The Farthest Shore” returns to the man’s world. The last three books of the series look at the man’s world and deliberately question its moral basis, even its reality.

However the word “feminist” has been misunderstood and vilified, it is feminism that we must thank for the inclusion of the whole human race in literature, rather than only half of it.

The fact is that women are still more likely to be at home than men are — maybe sewing, maybe sighing, maybe doing mathematics or playing the viola, but almost certainly also looking after the children and keeping food on the table and the floor swept. What is there to be ashamed of in that? In what way is it inferior to what men do? Women do not have to imitate men to be human beings.

What fiction mostly failed to do, for a long time, was to ask what happens there in the home, among the women? What is she sewing, and why? Does she want to, or not want to? Why does she unweave the tapestry every night? Is she sighing over her absent lover, or the bad state of the national economy, or the problem of the origin of evil? What is the life, the actual and the mental life, of half the human race?

If a man has no interest in the answers to those questions, then let him go read books for boys about battles, etc. – there are plenty of those.

Alejandro Serrano: Your work at Earthsea and other novels focuses much on the maturation of their characters and in their efforts to find their place in a cruel world full of dangers and whose balance tends to be volatile… This is only a reflection of the real life, transplanted to a world full of supernatural creatures, and that further enhances the universality of the social themes of your books. Much fantasy books focus on heroes without remorse or scenes where the spectacular eclipse any reflexions. Sometimes seems to be attempts to hide the lack of arguments of the writer, but your books centers in this reflexions… Fantasy should make us think about everyday life, about our relationship with the rest of the world?

Ursula K. Le Guin: I hesitate to say that any kind of literature “should” do anything; that is to reduce art to a practical service – teaching, inculcating morals — which is only one of its possible functions. So I’d say only that a fantasy that doesn’t somehow metaphorically explore our actual existence in the world is probably a trivial one. All the same, it could be amusing.

Alejandro Serrano: The role of women and men in western society has changed a lot in recent decades, approaching their living space one to the others, but… sometimes it seems that if we are not married, if we do not have children or stable relationships we can´t realize ourselves; and when we have children, both women and men have to work outside home, without time to educate children. Don’t you think that many times we are required too, both women and men, to fulfill their role at the family home and at work as if we were superheroes?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Yes. I see how terribly hard the generation of my children (now in their forties) work, wearing themselves out with duties, with very little time for quietness; and I feel deeply that something is wrong. But I do not ascribe it to the change in gender relationships at all. It is the work, and the nature of the work, that has gone wrong. I think men and women are caught in the great machine we have turned the world into – the capitalist machine of productivity/activity/growth which cannot ever cease for a single moment. The great machine that lays waste the Earth and devours its children.

Alejandro Serrano: All the books of the saga of the Western Shore (‘Gifts’, ‘Voices’ and ‘Powers’), will be published in Spain, according to the editor of Minotauro. At the moment, they only have traduced the first one, “Los Dones”, a novel that explore the nature of powers, personal growth and and tell us that them may conflict with the rest of the world. Our knowledge can be useful, but also the origin of our doom. This lesson is far from the usual vision of the powers in literature as a gift without condition: we must be careful when using them, they are dangerous. I don’t think that these books are targeted only to a youth audience, adults can learn something with this stories, and apply this lesson in real life, in our relationship with others. How many conflicts could have been avoided if we were more careful with our differences?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Publishers adore the “Young Adult” category, which has a secure audience among adolescents. Unfortunately, to publish a book in that category is to ensure that the critical establishment (even within science fiction and fantasy) will ignore it, and that many adults will avoid it, thinking that it is for children only. The fact is, many “young adult” books – particularly fantasies – differ from “adult novels” only in that their protagonists may be under twenty. I like writing about young people because they are open, vulnerable, their encounter with the world is fresh and passionate; but certainly I don’t feel that my books with young protagonists were written only for the young. (After all, consider Romeo and Juliet. . .)

Alejandro Serrano: While we wait for ‘Voices’ and ‘Powers’ in Spain, Minotauro will publish in late february of this year a book with some science fiction stories: ‘The Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin’ (“Los mundos de Ursula K. Le Guin), with ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ (“La mano izquierda de la Oscuridad”), ‘The Word for the World is forest’ (“El nombre del Mundo es Bosque”), and ‘The Dispossesed’ (“Los Desposeídos”). Do you feel there are substantial differences at the time of writing science fiction rather than fantasy? Can you tell us something about this stories?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Those three novels are all science fiction, not fantasy; that is, they take place in a universe that obeys the laws of physics as we know them, and do not openly violate scientific principles, as a fantasy may do with its wizards, or winged cats, or Alephs.

I consider fantasy to be the oldest kind of literature that is still practiced, and science fiction one of the youngest. Science fiction is an outgrowth of Realism. Like Realism, it uses the actual, often the contemporary, world as its basis. It differs from Realism only in extrapolating a future that might grow from this actuality, or imagining some plausible advance in science or change in society, which it then follows up in as realistic a fashion as possible. It’s a highly inventive and entertaining form of fiction, which I have enjoyed reading and writing.

I think science fiction is changing form, losing its definite intellectual outline, melting into other forms, as the world changes more and more rapidly around us, and fiction literally cannot keep up with the growth of science and technology, but only chase it.

Alejandro Serrano: There are sectors in our society (and in EE.UU.), who are trying to force people to political ideas that we thought to be overcome, such as religious fundamentalism, sexual taboo and their vision on justified violence. They pursue all those who don’t believe in the same way, they say that the country is under the lack of morality… Do you think that there is a moral far away to the religious or political fundamentalism, more socially tolerant and free thought? What role has fantasy in it?

Ursula K. Le Guin: I’ll say only that both science fiction and fantasy are forms of literature that permit the imagination of ALTERNATIVES – alternative societies, polities, cultures, rules of gender, ideas of religion, etc etc. And in doing so they have a great role in cultivating the rational use of the imagination, in freeing minds from the dead hand of rigid, irrational ideologies.

Alejandro Serrano: I don’t know what happens with the adaptations of Earthsea. Frankly, it is not so difficult to understand even the spirit of the saga (there are some things very interpretable), but every time someone tries to adapt it into other formats the result has nothing to be with what you have written. Not only happens to you, obviously, for example, recently Hollywood have completely destroyed the classic ‘I’m Legend’, by Richard Matheson. I think they should not adapt a book if they are not willing to preserve its spirit. The three movies of ‘Lord of the Rings’ by Peter Jackson are an exception… there are many things that they changed, but the spirit of J.R.R. Tolkien is in them. Even with the excess of violence and lack of deeply reflexions about it that are constantly present in the books, you can appreciate the beauty of life and what Sauron wants to destroy: thousands of small personal stories, all the good that exists in the world, that are beyond the survival of any kingdom. Do you think that in the future we will see a good adaptation of Earthsea, after the attempts of Goro Miyazaki and Lieberman? Nobody is interested in your own script with Michael Powell? What do you think about this two adaptations of Earthsea and Lord of the Rings’s one?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Ay, ay, carramba! Please! Don’t ask!

Alejandro Serrano: It seems that everything in Earthsea is said, and at times you have expressed your refusal to continue the saga, very understandable, on the other hand, after years of dedication to it. And frankly, although it could continue at the level of argument, it seems tightly closed. Have you ever thought about going back to write about Ged and Tenar, or spin-offs of some characters?

Ursula K. Le Guin: Well, as they say, “Never say never.” I love my people of Earthsea, and there are many islands I never had a chance to visit. . . But I do think the story finished telling itself completely at last in the sixth book.

Alejandro Serrano: The work of a writer never seems to be completed, if inspiration comes to … What projects do you have in mind?

Ursula K. Le Guin: My next book, which is to be published this spring, is “Lavinia.” She is the Italian girl whom Aeneas is fated to marry, and so found the city and the empire of Rome. The last books of the Aeneid are full of battles: Vergil had to tell about war and the insanity and tragedy of war, because (I think) he wanted to show his new Emperor Augustus the real cost of Empire, and ask him, Is it worth it? – But that didn’t leave him time to tell us much about Lavinia, or even let her speak. So, reading the poem, I began to ask Lavinia, who are you? And she told me. And that is the novel. It’s different from anything I ever wrote. I am very happy with it.

After that, I don’t know – I never know.

Alejandro Serrano: Finally, it has been a pleasure to know you… What would you say to your fans in Fantasymundo and to those who have not yet read your books?

Ursula K. Le Guin: A writer without readers is a miserable creature. If you are happy reading my books, believe me, I’m happy that you read them! And happy that you and I meet thus, in a mysterious way — the only true magic I know – in the space of literature, where minds and imaginations meet, and join, and play together, and (even though we are forever strangers – even though we speak different languages) we understand each other.

I have enjoyed this interview. Many thanks!

Ursula